(Blogger’s note: I don’t usually write about or review books. But here’s the story of an excellent memoir I recently finished.)

As a Russian aristocrat, Paul Grabbe grew up in a lost world.

His family lived in palatial residences in St. Petersburg and the Russian countryside. They were waited on by a staff of footmen and cooks, maids and tutors — a life so cosseted his mother never even brushed her own hair till they left the country. His father, a famous Russian general, was an intimate of the last Russian czar Nicholas II.

In 1917, Paul and the rest of his family watched the Russian Revolution begin from their apartment in St. Petersburg. Their world was ending, but they didn’t know it at the time.

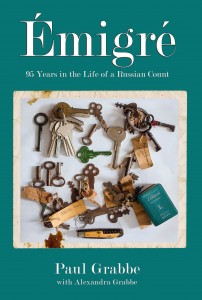

The recently released memoir Emigre: 95 Years in the Life of a Russian Count is the story of Paul Grabbe’s remarkable life. It follows him from his early years in Russia through his wanderings in Europe, then the United States.

For years, Paul and his family assume their exile is temporary and the Bolsheviks will lose power. One day, they’ll return to their homeland and their old lives will resume again.

So Paul, young and adventuresome, journeys to Colorado in the 1920s, where he works as a waiter in a TB sanitarium, a gold miner, and a tutor. He goes to California, where he tries to break into the movies as a screenwriter. Instead, he finds work in a plush cemetery, tending the dead and the bereaved. When he becomes unemployed, he’s so broke he almost starves to death.

From job to job, place to place, Paul Grabbe spends his spare time doggedly pursuing knowledge and mastery of the English language. He falls in and out of love. After a while, you kind of give up and fall in love with him yourself — this privileged young man who loses everything, but grows up quickly and learns to make his own way in a harsh new world.

Paul Grabbe died in 1999, leaving behind this manuscript. His daughter, writer Alexandra Grabbe, added photographs and published this vivid memoir early this year. Here, she answers questions about her father and the book he didn’t live to see.

Did your father talk much about his past to you and your family?

My father did not talk much about his family and past until I was grown up. I think he finally began talking about it when my mom pushed him to write his memoir. Then, they did a project together, based on my granddad’s photos, Private World of the Last Tsar. (My mom was an English major at Vassar and had worked as an editor.)

My kids have had many friends whose parents were from other countries, and I’ve often noticed the difficulties for parents and children who come from both different generations and different cultures. Do you think you can ever completely understand someone from a different culture? (Of course, this raises the obvious question whether you can completely understand someone from a different generation. Maybe you can’t.)

I do think it is difficult to understand someone from another culture, but it all depends, like on where you live. If you live in the other person’s country, it is harder. I feel as if the cultural differences with my ex were why we broke up, as much as his betrayal with my “best” friend (preview of my novel, if I ever get an agent.)

I don’t think you can generalize though, as it depends on the situation and the people. Flexibility required. By the time my parents met, my dad was ready to do some therapy. He still went to therapy into his nineties.

Readers can’t help falling a little in love with your father as he makes his way through this country. He’s amazingly resilient, hungry to learn, keeps pushing on, no matter what. Did he ever wonder what he would have been like — how different — if there had been no Russian Revolution and he had remained an aristocrat?

No, he really never looked back once he was married to my mom. He never made a big deal about his past or having been a member of the aristocracy or having lost a fortune. He was very humble, which comes across in the memoir. (If there had been no Revolution, he would not have met my mom and I would not exist.)

For me, the most vivid writing in the memoir comes as your father tackles life in this country. In contrast, his childhood and youth in Russia don’t seem to have the same kind of immediacy — they’re more like a remembered dream. I’m wondering if this isn’t just the passage of time. Did he not want to remember it too vividly? Was it too painful?

I don’t know the answer to this question. I can theorize that maybe, maybe some of it has to do with my editing skills. I did edit down the manuscript considerably, but touched the first part less, since it was already published, although not distributed since the publisher went bankrupt.

Your father died more than 15 years ago. Do you feel he’s finally at rest after you published this lovely memoir?

It was important to him to finish the memoir, so I think he would have really appreciated that I got it out there for him. He hoped people could learn from his experience, I think. The part about being an immigrant I found particularly moving.

And your next project?

I’m writing a short story collection about how the Revolution affected the children and grandchildren of members of the aristocracy in their lives outside Russia.

(Copyright 2015 by Ruth Pennebaker)

I

I also read and enjoyed this memoir, which reads like a novel. What an amazing story.

This sounds like a fascinating story; so glad Alexandra was able to get it out there.

It’s a charming read.